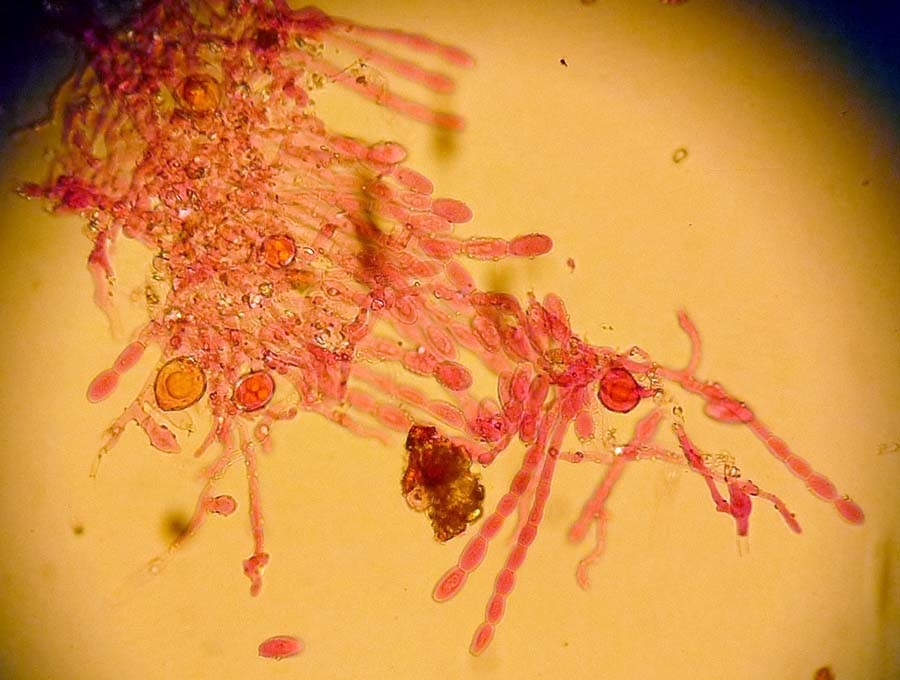

Powdery mildew spores on wheat – the second most important food crop in the developing world after rice (Copyright CABI).

At first glance it might be hard to see how the exploitation of microbes, especially fungi, can have the power to help humanity meet the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), feed the world’s growing population and improve the bioeconomies of poorer nations.

But a team of international scientists from CABI, the Westerdijk Institute and the US, led by CABI lead author Dr Matthew Ryan, have come together to pen a new paper in the World Journal of Microbiology and Biotechnology, which examines the challenges and opportunities of putting fungal biological resources right at the centre of supporting international development.

Dr Ryan, Curator of CABI’s Genetic Resource Collection, which boasts 30,000 strains from over 140 countries including 2,900 that originate from Africa, says the role fungi play in feeding the world should not be underestimated. Quite simply, the fungi and their role in the food chain is vital to global food security.

“International Biological Resources Centres (BRC) underpin research and development and the global bioeconomy. BRC are well placed to underpin infrastructure to aid governments as they strive to deliver their commitments to the SDGs,” Dr Ryan said. “However, to achieve this they must not only consolidate their existing capacities but evolve their approaches to meet the ever-changing requirements of their users, particularly in biodiversity-rich, developing countries.”

Co-author Dr David Smith examines some of the cultures in the UK’s National Culture Collection housed at CABI’s laboratories in Egham. CABI acts as custodians of microbial genetic resources on behalf of its member countries, many of which are Low to Middle Income (LMIC) countries in Africa, Asia and the Caribbean.

While microbial collections of living fungi, viruses, yeasts, and bacteria are spread throughout the world, there is a distinct challenge in redressing the imbalance of collections held within countries in the developing world.

Of the 739 collections listed on the World Data Centre for Micro-organisms (WDCM), for example, only 17 WDCM-registered collections exist in Africa and, of these, just two are fungal while the others are general microbiological collections. Furthermore, while the collections in Africa hold a total of 28,650 strains, 89 percent of these are held by just two countries – South Africa and Egypt.

Dr Ryan added, “The vast majority of countries in the developing world simply do not have the infrastructure in place to manage and operate their own culture collections.

“Other major collections, such as the Westerdijk Fungal Biodiversity Institute and the Fungal Genetic Resource Centre (FGSC) amongst several, play individual roles in supporting the maintenance of global microbial diversity but without appropriate infrastructure on a global scale this cannot be performed effectively.

“The Nagoya protocol, now ratified by 117 countries, aims to ensure that benefits arising from use of countries’ genetic resources are shared but differences in interpretation and implementation mean that it has resulted in unintended regulatory barriers.

Beyond that, not all countries have the economic resources to support such activities which may actually require collaborative, regional or international approaches. We also need to provide infrastructure to support microbiome research, which is intrinsic to many SDGs and which traverses the fields of human health, medicine and agriculture.”

Co-author, Dr Smith says that harnessing fungi for use by humankind to enhance bioeconomies in Low LMICs is a pre-requisite and, while collections such as CABI’s allow LMICs to deposit their strains, there is a pressing need for capacity building in the developing world for such states to be custodians of their own biological resources.

“A more urgent challenge remains in finding funding for BRCs to underpin research and good science which compete against perceived greater priorities such as food security or academic research,” Dr Smith said. “Innovative funding mechanisms and efficiencies in coordination and management are required to secure the microbial resources on which these depend.”

The authorship team, in looking at ways in which LMICs can maintain their biodiversity and handle their data, suggest a range of recommendations including investment in new technology and training in taxonomy, data handling, bioinformatics, biological resource technology and management.

Additional information

Full paper reference

M.J. Ryan, K. McKluskey, G. Verkleij, V. Robert, D. Smith, ‘Fungal biological resources to support international development: challenges and opportunities’, (2019) 35:139, World Journal of Microbiology and Biotechnology, DOI: 10.1007/s11274-019-2709-7

The paper is available to download as a free open access document.

Video

Dr Matthew Ryan, Curator, Genetic Resource Collection, CABI talks the UK’s National Culture Collection as part of a Science Museum special exhibition ‘Superbugs’.

[youtube https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Si4K15ugNiw&w=560&h=315]

Related News & Blogs

Transforming agriculture with drones: empowering youths for a sustainable future

On this UN World Youth Skills Day 2023 (Saturday, 15 July), we celebrate the transformative power of skill development in shaping the lives of young individuals and creating a brighter future, writes Violet Ochieng’ – winner of the Carol Ellison Scienc…

14 July 2023