By Stephen Blakeway

As a tourist how can we assess whether the animals we see have good welfare, and ideally, ‘a good life’?

Recently, I’ve been a tourist in Mexico and Jordan, and, having contributed to ‘Tourism and Animal Welfare’, I took the opportunity to think more about this question. As my interests are animals and their relationships to us, each other, and their environment, I spent a lot of time observing.

In Petra in Jordan when I was visiting, I accidentally came too close to a dog who was asleep by a donkey among a group of other donkeys, and he jumped up and went berserk at me. I quickly moved back while the donkey placated him by rubbing his head against the dog’s flanks and neck. The dog, leaning into his companion in apparent ecstasy, licked the donkey’s nose and settled back down to sleep again.

In Petra, Jordan, a donkey placates his canine friend who has just woken with a fright. Photo taken by the author.

A young man gave his camel a can of soda and some flat breads, then jumped on to his back and they loped off together, apparently easy and relaxed with each other, in contrast to the more wary behaviour between another man and the two camels standing alongside him. The different relationships owners have with their animals can make a significant difference to how much they all enjoy their lives.

A young herder higher up the mountain showed me through his binoculars the cave on a precipitous adjacent ridge where he herds his uncle’s goats. He told me something of his life and the lives of his animals, including his young dog which he’d reared from a tiny puppy. He set off on his donkey, together with his pup, into the cleft of a hill and a short while later, re-emerged behind a vociferous collection of sheep and goats who streamed out across a small basin of flat ground towards their daily ration of grain.

A knowledgeable local café owner told me about the birds that live around Petra, the places where grouse meet in groups, and about a spring in the hills where a procession of species comes to drink at dawn. With so much local knowledge we talked about the potential for developing eco-tourism in the area.

In Ventanilla in Mexico, my local community eco-tourism guide spoke passionately about the 50 or so local bird species he showed me, and about his community’s initiative to restore their mangrove lagoons after two devastating hurricanes. He was vociferous in criticising a neighbouring project that kept crocodiles, iguanas and turtles captive just to make money from tourists, particularly when, with a little effort, they can all be seen living wild in the local lagoons.

While it is difficult to assess ‘a good life’ from the short interactions we have with animals as tourists, all of these observations say something about longer term relationships. It takes time and stability for a dog and donkey to develop a friendship, or for someone to get to know the nature around his home as thoroughly as some local people.

Alongside observing animals’ behaviour, their body condition says something about their nutrition and metabolism; their wounds, scars and coat condition, and ease of movement, lameness, and the lumps and bumps around tendons and joints – all say something about how they have been used throughout their lives; and discharges and other more detailed observations add something more about their health and disease. When we learn to read animals, they can tell us about their lives.

When we spend more time with local people, building the trust that allows more open conversations, we can find out more about the life of the whole community. We begin to understand why things are as they are, for themselves and their animals, giving us clues about how things might get better or worse over time, and helping us as tourists to contribute more positively to the overall well-being of local communities.

While it can be human nature to pick up on faults, when we look, there is often much that is good to be seen and built on. Of course there are tourists too large for the donkeys trying to carry them, dogs can be over-bred and spend their lives tied up or for ever on a lead, and the food on our plates may come from agricultural animals living forever in the twilight world of factory farms.

As tourists we are the lucky ones. As nothing we do as a tourist is essential, we can make positive choices. The points above, summarised on the ‘Hand’ diagram can provide a simple framework to help us assess what we see.

A guide to assess animal welfare. Provided by Stephen Blakeway.

The authors acknowledge the work of The Donkey Sanctuary in developing and spreading the use of the Hand through its international work.

Stephen Blakeway is a Self-employed One Welfare Specialist based in Devon, UK. A veterinarian, animal welfare scientist, and qualified teacher, specialising in practical approaches to improving animal welfare, strengthening human-animal relationships, and extending the reach of veterinary services.

His chapter on ‘Donkeys and Mules and Tourism’ is included in the Tales from the Front Line in our new book, Tourism and Animal Welfare.

Related News & Blogs

Tourism and animal welfare: a 21st century dilemma

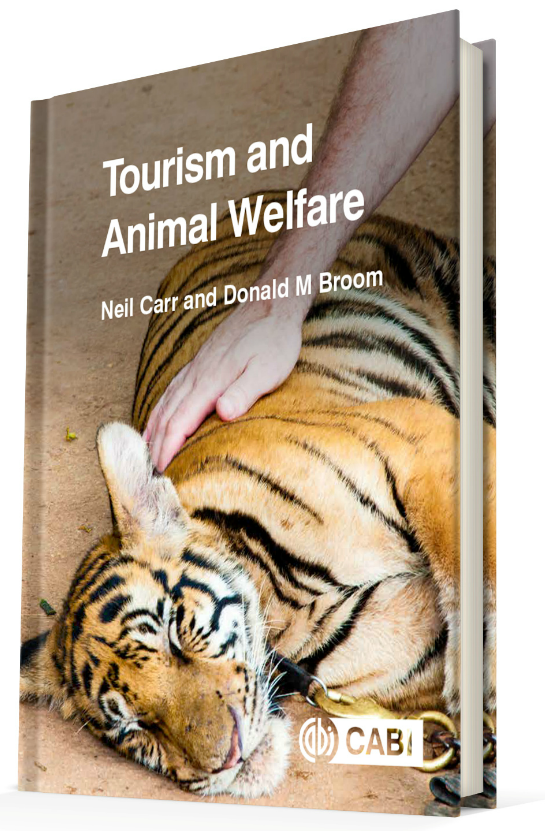

Tourists encounter animals in many different situations: photo opportunities, street performances, animal rides and specialised ‘sanctuaries’ such as elephant homes and tiger temples. Tourism may benefit wildlife, by funding wildlife animal conservation, as well as providing vital income for local communities, but the exploitation of animals in animal entertainment can be a cruel and degrading experience for intelligent sentient creatures.

13 February 2019