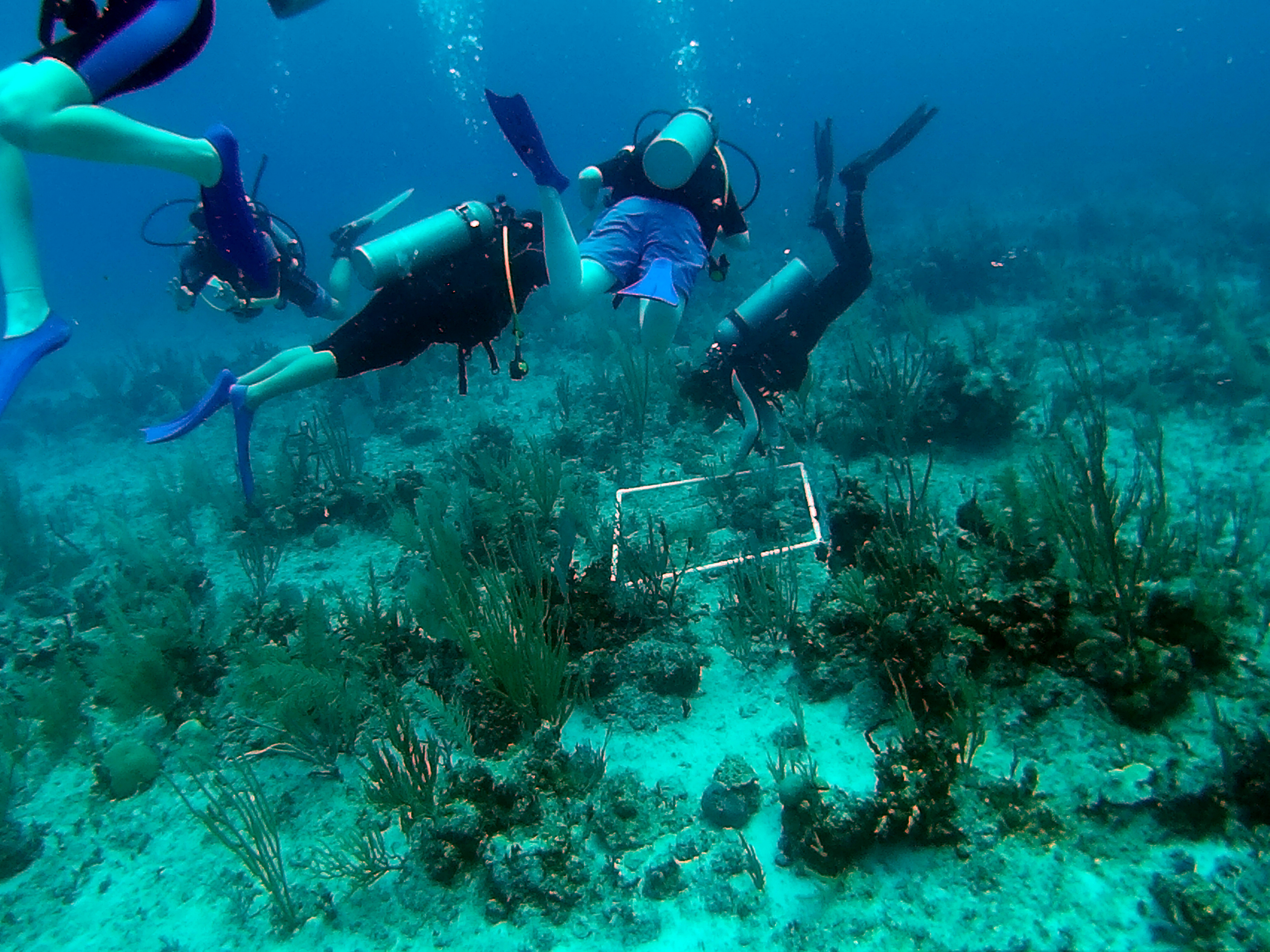

Scuba quadrats. Image credit: David H. Williams, Rye St Antony

Scuba quadrats. Image credit: David H. Williams, Rye St Antony

Our guest blogger this month is David Williams, who is the Head of Science at Rye St Antony School, Oxford. He recently led a group of schoolgirls on an Operation Wallacea expedition to Mexico, where they took part in a conservation project which involved conducting mammal surveys and assessing the impacts of tourism on turtle populations and coral reefs. David tells his story as a diary looking at events over the two-week expedition.

I was delighted to be asked to blog on this subject. One of my student’s parents works at CABI (Centre for Agriculture and Biosciences International) – an organisation that focuses on the environment and biodiversity. As an editor at this organisation, she saw the opportunity to highlight the work of schools and conservation. I’m keen to promote science both as a career and as an interest for life, and feel that this is best done by encouraging an appreciation of science as a real, relevant and ongoing subject. My story starts here …

Thursday: Returned to the UK on Monday and finally feel normal. Washing done, dive gear stowed and 2000+ photos narrowed down to 400+ highlights. Take your pick of clichés – trip of a lifetime; once in a lifetime opportunity; life-changing experience. They’re clichés for good reason. My party of 16 schoolgirls (aged 16 to nearly 19) would subscribe to them all. I’ve run DofE, trips to Belgium, Spain and all over the UK, adventure, science, history, geography and language trips. I’ve sent my own children on a school trip to Kenya, a rugby tour to South Africa and on a challenge expedition to India. Taking this party from Rye St Antony School in Oxford to Mexico with Operation Wallacea (Opwall) has topped them all.

Opwall is a conservation research organisation funded by academic partnership with school and university students, running biological and conservation management research programmes in remote locations worldwide. Teams of university academics are concentrated at the study sites, and paying volunteers effectively fund their work whilst gaining experience of how scientific research works in the field. Research is independent of normal academic financial sources, thus breaking the funding/publishing cycle that can discourage research and prevent long-term projects. Work is peer-reviewed and published. Opwall has facilitated the discovery of, for example, 30 vertebrate species and the rediscovery of 4 ‘extinct’ species, along with the identification of species previously unknown in an area.

Monday: Cancun. Overnight stop before we head to the jungle. We’re not in Kansas anymore – two of the girls are a little late back from their free hour on the time. Out waiting for them I am offered drugs and worse by several keen vendors. It will be good to be somewhere where the hazards are only toxic, venomous or infectious.

Tuesday: Our jungle camp, KM20 (20km in from the entrance to Calukmal Bioreserve), is a ramshackle arrangement of semi-permanent buildings, tents, hammocks and tarps. There’s limited access to rainwater showers, composting short-drop loos and a kitchen of sorts, but no running water so the girls are learning to wash hands in buckets of dilute bleach. Food is brought in from a nearby village, lots of beans, tortillas and chicken that looks to have been macheted that morning. The science staff are welcoming, but immediately it is underlined to us that we are there to assist in their research – this is an expedition, not a holiday. Some of the surveys leave early – birds, mammals and some get in late – bats, lizards/snakes/amphibians or herps as we soon learn to call them. We are expected to be timely, organised, equipped and ready to work hard. We are instructed about jungle safety. The chief dangers are heatstroke and dehydration. We do eventually learn to love our hydration salts, and to respect the need to cover up. There are the dangers of ticks, chiggers and the dreaded maggots-growing-inside-you botfly. Even the trees are out to get you. The Chechen tree (Metopium toxiferum) with its blister-causing acidic sap is all around. Fortunately so too is its counterpart, the Chaca tree (Bursera simaruba) also known as the tourist tree for its red, peeling bark. The alkaline sap of this tree can be boiled into a balm to provide a jungle remedy for Chechen poisoning.

Chechen and Chaca trees. Image credit: David H. Williams, Rye St Antony

Chechen and Chaca trees. Image credit: David H. Williams, Rye St Antony

Wednesday: Tracking mammals with Luis, a Portuguese masters student who is jungle-crazy but incredibly knowledgeable, along with his two dissertation students. Jaguar, coati, agouti, deer and tapir are all identified by the girls after instruction. We trek 4km in the jungle heat and humidity, slowly when tracking then at a run to catch the bouncing pick-up truck back to camp. A helmeted basilisk is spotted. We get through a lot of DEET-free insecticide. Back at camp camera-trap photos are analysed by the girls with a glimpse of the elusive jaguar eliciting a cheer. The work is important to understanding how the mammals are affected by the five-year drought that the area has experienced. Rare species are migrating towards wetter areas, and knowing their routes is a crucial step towards safeguarding them – advising on hunting and on green corridors across or under highways, for example. Whilst at no stage do we see a final result, at each stage it is explained to us why this is important work – how the local community, the bioreserve, broader conservation and government advice are all depending on these data. This is real.

Friday: Mayan ruins provide a break from surveys. We have trapped, identified and logged butterflies, birds, bats and herps, studied jungle survival and investigated habitats. There have been daily lectures on aspects of jungle ecology and the past and current research projects of the scientists working with us. We are immersed in applied biology, ecology and conservation. We have seen how OpWall’s work has helped government to refuse a highway through this reserve, how the funding model allows long-term research projects to flourish. The effects of climate change are central to much of the work, particularly in linking the changes in habitat to the resultant population changes in some of the species. Consideration as to helping the area to adjust is important – for example, asking whether the provision of temporary manmade aguadas (watering holes) is sustainable. Research that we are carrying out will be used to help the bioreserve to make decisions that affect the flora and fauna, but also the local people in this unique area. Some of the girls are talking of changing their university plans. This is life-changing.

Glossophaga soricina. Image credit: David H. Williams, Rye St Antony

Glossophaga soricina. Image credit: David H. Williams, Rye St Antony

Tuesday: The beach is a relief from the jungle, but not a rest. Qualified divers among us are on the reef identifying corals and assessing the effects of tourism on the turtles. Estimating numbers of turtles in the area and monitoring how the tourist numbers and behaviours affect the turtles is a key issue. Tourists like to touch the turtles and worse – some have been seen trying to ride the turtles. The beach is closed at night to allow turtle nesting, and some of our girls are fortunate enough to have been out with the researchers marking and laying cordons around nest sites. During the day others are converting school pool training into a full PADI qualification, some are taking the qualification from scratch, others are working on the surface, snorkelling over the reef. Two or three lectures every day are making us knowledgeable reef ecologists. This is education.

Wednesday: We’ve all done quadrats at school, counting daisies. At 15m below, assessing live coral cover on the reef we can see that it is a technique in daily use by real scientists – by us, in fact. Later we descend with the ‘Queensland Colour Chart’ of corals to secure data on bleaching of corals. One of the research assistants dives with us. This is, after all, information which will help her to write her dissertation. Again it is underlined that we are an essential part of the research efforts here: we are not tourists. This is science.

Saturday: Dinner out. Talk of what we have learned, of plans for university and of extended projects. Talk of Summer 2018 – Ecuador, the Galapagos? Fiji? Madagascar? Exciting prospects for sure, but all agree that the feeling of having learned so much and of contributing to real scientific research have been the biggest excitements.

Editor’s note

David’s diary illustrates the dual goals of conservation of biodiversity and sustainable tourism. These align with CABI's interests within these areas, both development projects and knowledge business (database and book publishing).

Current CABI projects include:

Rescuing and restoring the native flora of Robinson Crusoe Island

Controlling the invasive blackberry on the Galápagos Islands

Further information on sustainable tourism is available to subscribers of the CABI Environmental Impact database. A selection of these records is provided below:

Bell, C. D.; Blumenthal, J. M.; Austin, T. J.; Ebanks-Petrie, G.; Broderick, A. C.; Godley, B. J. Harnessing recreational divers for the collection of sea turtle data around the Cayman Islands. Tourism in Marine Environments (2009) 5 4 245-257

Boley, B. B.; Green, G. T. Ecotourism and natural resource conservation: the 'potential' for a sustainable symbiotic relationship. Journal of Ecotourism (2016) 15 1 36-50

Duyen Thi Thu Tran.; Nomura, H.; Yabe, M. Tourists' preferences toward ecotourism development and sustainable biodiversity conservation in protected areas of Vietnam – the case of Phu My protected area. Journal of Agricultural Science (Toronto) (2015) 7 8 81-89

Momir, B.; Petroman, I.; Mergheş, P. E. Ecotourism – a major factor in the preservation of flora and fauna biodiversity in Banat. Management Agricol (2014) 16 4 98-103.

Schloegel, C. Sustainable tourism: sustaining biodiversity? Journal of Sustainable Forestry (2007) 25 3/4 247-264.

Shinde, A. S.; Pardeshi, R. S. Eco-tourism: conservation of biodiversity in Maharashtra. Golden Research Thoughts (2015) 5 2 GRT-6048

Zaú, A. S. The conservation of natural areas and the ecotourism. Revista Brasileira de Ecoturismo (2014) 7 2 290-321.

Related News & Blogs

Transforming agriculture with drones: empowering youths for a sustainable future

On this UN World Youth Skills Day 2023 (Saturday, 15 July), we celebrate the transformative power of skill development in shaping the lives of young individuals and creating a brighter future, writes Violet Ochieng’ – winner of the Carol Ellison Scienc…

14 July 2023