Copyright: John & Penny Hubley

Copyright: John & Penny Hubley

This blog is contributed by Dr Neil Pakenham-Walsh, Coordinator of HIFA2015 , the global campaign and email forum focussed on informed healthcare provision in developing countries. We in richer countries take for granted that our healthcare providers have access to the information they need to make informed decisions...

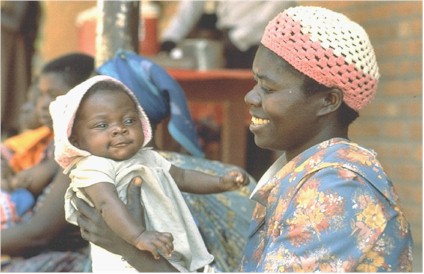

Every person has access to a healthcare provider. (Nearly every person – there are sadly a number of people who are destitute, utterly alone and abandoned by everyone around them.) I use the term ‘healthcare provider’ to mean anyone who is responsible for providing care at any moment, including and especially parents and family caregivers. Even the very poor have access to a healthcare provider.

The problem is, if you are one of the world’s majority poor, the chances are that your healthcare provider will be uninformed. As a result, you are likely to receive ineffective or harmful care, and you may die simply as a result of this care.

You are most likely to die in the home or local community, without seeing a trained health worker. The most high-level healthcare provider present in your final hours and minutes may be your mother, a family caregiver, a traditional healer, a village health worker or perhaps a midlevel health worker. Their decisions will mean the difference between life and death, between your living for another day or becoming a statistic - one of the tens of thousands of children and adults who die prematurely and unnecessarily every day in low-income countries.

Let's look at the healthcare they provide:

– Mothers and fathers are the most important group of healthcare provider for a baby or young child. Consider this: In Maharashtra state, India, a survey 1 found that 4 in 10 mothers believed they should *withhold* fluids if their baby developed diarrhoea. It is tragic that these mothers are unknowingly contributing to the deaths of their own children. 1.8 million children die unnecessarily from diarrhoea every year.

– Parents and children often have the support of the extended family. Yet consider this: 8 in 10 caregivers in developing countries do not know the two key symptoms of childhood pneumonia – fast and difficult breathing – which indicate the need for urgent treatment. 2 Furthermore, only 20% of children with pneumonia receive antibiotics despite wide availability. 2 million children die unnecessarily from pneumonia every year.

– It is often said that 80% of Africa's population rely on traditional healers but it is less often said that these same populations also have the highest rates of premature death in childhood and early adulthood. All too often, the treatments from traditional healers are ineffective and may be harmful. Furthermore, treatment by traditional healers results in long delays in seeking care at health facilities.3 Every doctor and nurse who has worked in a district hospital in South Asia or Africa is familiar with the arrival of patients dying from advanced infection, bleeding, or cancer – if only they had attended earlier, there would have been a chance to save them.

– Those who do reach the attention of a primary health worker are by no means assured of effective treatment. This may be because of lack of essential drugs or equipment, but it is often primarily due to lack of knowledge. More than half of patients attending primary health centres in India were incorrectly prescribed a harmful treatment.4,5

– The few who reach a doctor in a district hospital may not receive appropriate treatment either. Three in four doctors caring for sick children in district hospitals in Bangladesh, Dominican Republic, Ethiopia, Indonesia, Philippines, Tanzania, and Uganda had poor basic knowledge of leading causes of child death such as childhood pneumonia, severe malnutrition, and sepsis.5

If this situation existed in the USA or Europe, there would be a monumental outcry. In developing countries, there is silence – few are even aware of the fact that their right to informed health care is being denied; no-one is held to account.

The situation is not the fault of healthcare providers. No mother, family caregiver, health worker or doctor can provide effective care unless they are empowered through a basic minimum of healthcare knowledge and resources.

What can be done? We, the international community and governments need to focus all our efforts on understanding and addressing the needs of healthcare providers in resource-poor settings, especially on the 57 countries with critical shortages of health workers. Engage them, give them a voice, listen to them, bring together all stakeholders to better understand and address their needs, collect evidence of what works and what doesn't, and advocate for the change needed to empower them to make the right decisions for those who are under their care.

The late WHO Director-General Dr Jong-Wook Lee put before us a vision, which has been adopted by the Global Health Workforce Alliance: 'All people everywhere will have access to a skilled, motivated and supported health worker, within a robust health system'.

Let's work together towards this vision. Join the global campaign and email forum, Healthcare Information For All by 2015. We are more than 3000 health and development professionals from 2000 organisations in 157 countries. Work with us for a future where every person has access to an informed healthcare provider – a future where people are no longer dying for lack of knowledge. www.hifa2015.org

Dr Neil Pakenham-Walsh, Coordinator, HIFA2015, neil.pakenham-walsh@ghi-net.org

References

These references can be found on CABI's Global Health database.

- Wadhwani N. An integrated approach to reduce childhood mortality and morbidity due to diarrhoea and dehydration.

- Wardlaw T et al. Pneumonia: the leading killer of children. Lancet 2006;368:1048-50

- Nakahara, S. et al. Exploring referral systems for injured patients in low-income countries: a case study from Cambodia. Health Policy and Planning 2010;25:4:319-327

- World Bank.India Development Policy Review 2006

- Yeom JongHum et al. Identification of inappropriate drug prescribing by computerized, retrospective DUR screening in Korea. Annals of Pharmacotherapy 2005; 39:11:1918-1923

- Nolan T et al. Quality of hospital care for seriously ill children in less-developed countries. Lancet 2001;357(9250):106-10

Related News & Blogs

How can we inspire young people to pursue careers in agriculture?

Recently I had the opportunity to return to my old university – The University of Sheffield – and take part in a networking event for early career researchers in plant physiology. The event was fully booked and attended by people soon to finish their u…

9 March 2017