Urban Agriculture and its Role in Community Building

A.M.G.A. WinklerPrins

Urban agriculture (UA) is about much more than producing food, it is about growing communities and empowering people. The social interactions needed to grow food in urban settings, whether in organised community gardens or allotments, in abandoned lots, sacks, balconies, or berms, brings people together when they might otherwise not have, and this enables them to build trust and community where these notions may be only tenuous. Case material from around the world, in the more developed Global North as well as the Global South, demonstrates this important role for urban agriculture no matter the community. The food produced may alleviate food insecurity and provide access to healthier foods, all of which is important, but perhaps even more valuable is the social interaction fostered via the need to manage spaces of urban cultivation, which can overcome differences between new neighbours and also be leveraged by communities to mobilise for other purposes.

A personal vignette

When I first moved to Los Angeles, I went seeking greenspace in the concrete metropolis. While the large green parks were long walks away from my apartment, just a few minutes outside my front door was the ‘pocket’ Unidad Park.

Unidad is dominated by a playground and seating area. But, sitting at the back of the park and surrounded by a low fence lies a wedge-shaped green area with 12 raised beds. When standing inside this tiny urban garden, the buildings of downtown Los Angeles fill the skyline.

The beds teem with heterogeneous offerings: California succulents, roses in bloom, potatoes, mint, leeks, and even young fig trees. All of this belongs to the Unidad Park Garden members.

After finding the park, I decided that joining the community garden would be a great way to learn more about gardening and a way to get to know my newfound neighbourhood. A sun-faded phone number on the park bulletin board yielded that meetings were the first Saturday of each month, and attendance was all it took to join.

When I arrived at my first meeting, the warmth of the gardeners was immediate. Did I have much experience? No, not a problem, there are classes on Saturdays to help me get started. Did I want some food or coffee? Here, have some. Did I want to help with a plot until I could get my own? Rosa is willing to share. Despite a serious language barrier — the garden leaders speak Spanish, and I do not — the small team of gardeners gave me access to the garden and welcomed me to the neighbourhood.

I now check on the garden a few times a week to pick up trash, weed the plots, and water the plants. The leeks and mint have made their way to my kitchen, and I've started taking Spanish lessons. Every meeting teaches me more about my neighbourhood, the plants, the people who have made the garden their own, and by extension the new city in which I now reside.

By L.T. WinklerPrins (24), a recent arrival in Los Angeles, CA

About the book

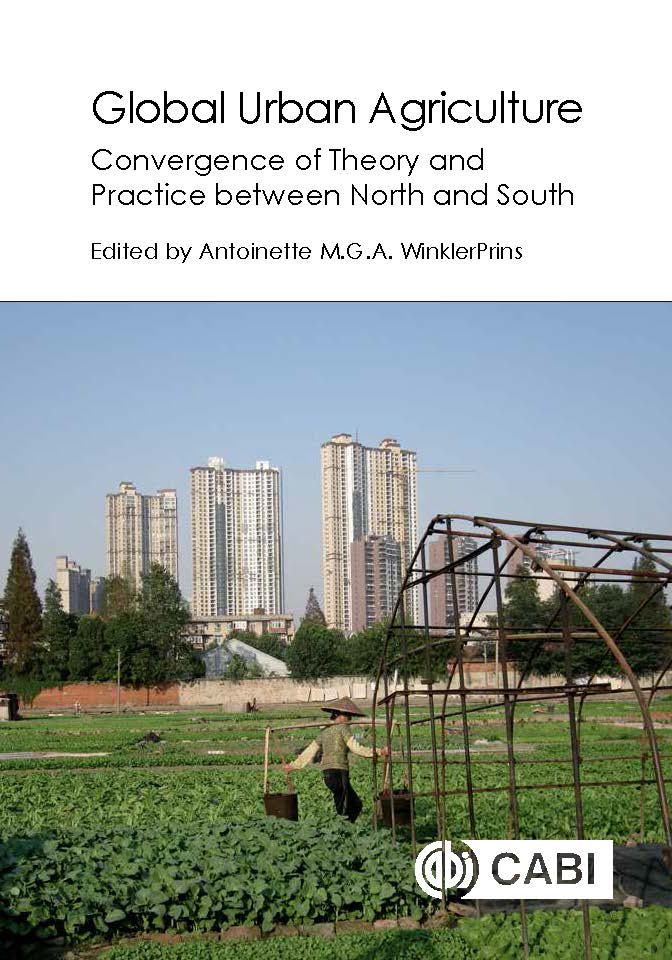

In one of the first books to consider urban agriculture in a global context, this book brings together material from around the world, illustrating how urban agriculture is much more than growing food. The book opens with an introductory chapter (WinklerPrins) defining urban agriculture and discussing how the topic has been differentially treated around the world, comparing and contrasting UA between the Global North and South.

The first few chapters (White and Hamm; Gray et al.; Parece and Campbell) provide focused overviews of the role that urban agriculture plays in the broader context of urban food systems, including the importance of community gardens. The next few chapters in the book unpack given notions within urban agriculture such as the difficulties of defining ‘community’ consistently (Bosco and Joassart-Marcelli), illustrating the difficulties in consistently mobilising labour for UA (Broadstone and Brannstrom), and developing adequate markets for UA products (Bellwood-Howard and Nchanji). The next few chapters engage with social and environmental sustainability with LeDoux and Conz illustrating a strong link between UA and social justice while Lowell and Law consider how the concept of sustainability is or is not fully engaged in UA; Byrne et al. consider how UA maintains urban ecosystem services while White illustrates how UA creates greater resilience in urban systems.

Other chapters in the book illustrate a number of less expected elements of UA but all contribute to the idea that UA builds community. McLees focuses on the dynamism with which UA is practised while Hammelman links UA to ideas of ‘world cities’ and Gallaher demonstrates how UA creates green spaces even in one of the world’s densest slums. Albov and Halvorson link UA with urban community supported agricultural practices while Dryburgh deliberates the complex role of bees in the city. The chapter by Horowitz and Liu considers the challenge of UA as illegal activity while Mujere points to how UA’s success can be undermined due to political affiliations of its practitioners. Chan et al. elaborate further on the idea of UA as a form of resilience by considering how community gardens are socio-ecological refugia.

In the concluding chapter of the book, WinklerPrins emphasises the point that urban cultivation is much more than producing food and, because of this, points to the need for legal and social acceptance of UA as an urban livelihood, desirable not only for social reasons but also for contributing to the greening of the city and longer term environmental sustainability of cities everywhere.

All photos: L.T. WinklerPrins, March 2017.