Yesterday (25 January) saw CABI’s first venture into organizing a symposium in the field of tourism, with a stimulating line-up of speakers assembling at London South Bank University, the co-sponsor and host institution of the event. Tourism is one of the fastest growing sectors of the global economy, and has particular importance in many small nations in regions such as the Caribbean and Pacific, and also as one of the largest sources of foreign exchange in a high proportion of the world’s least developed countries (LDC’s). But is the growth fair and sustainable, and who are the main beneficiaries? All too often the jobs created by tourism, although welcome, are low-paid and seasonal, and contrasts those working in the industry with the comparative wealth of those participating as tourists. Tourism also brings social and environmental pressures, and recent years have seen rising levels of protest in destinations where residents see their lives being unduly affected by ever-increasing visitor numbers. Thus the symposium, under the theme of social justice, considered issues of equity and fairness in tourism destinations, how the industry can work for destination communities and employees, and how it can be a force for good if managed properly and with foresight.

Social justice is defined by the Oxford English Dictionary as “Justice in terms of the distribution of wealth, opportunities and privileges within a society.” A charity which has been working since 1989 for ethical tourism which promotes social justice and gives a positive experience for both travellers and the people and places they visit is Tourism Concern, and Executive Director Mark Watson gave the first presentation of the symposium. He gave an overview of some of the campaigns Tourism Concern has conducted (e.g. on porter’s rights, volunteer and orphanage tourism, indigenous peoples, water equity, and all-inclusive tourism). All of these campaigns are part of the overall mission of ensuring that tourism always benefits local people, protects rather than exploits destinations, and by doing so gives a better experience for travellers themselves. Good tourism is a two-way relationship in which tourists give back to the communities they visit, and are enriched by interaction with local people and experience of their cultures and the places where they live. In a time when economic development is so often seen as the main priority, Mark joined with other speakers in calling for tourism teaching and research to consider tourism as a driver for positive social change, not just as a means of employment.

Johannes Novy from Cardiff University spoke from an urban planning background about the impacts of tourism, and how these have sometimes led to protests against the industry in cities including Venice, Barcelona, and his own city of Berlin. Like many other tourism destinations, he said that Berlin for a long time didn’t acknowledge the unease felt by sections of the population, but saw the role of the destination as creating the conditions in which the private sector could bring in employment, purchasing power, and tax income for the city. While 85% of Berlin residents don’t feel disturbed by tourism, the impact of the industry is unevenly distributed, with up to 40% of locals expressing concern in the parts of the city most heavily impacted. Tourism can lead to over-crowding, lack of services for residents as shops and local businesses focus on the lucrative tourism market, displacement of traders and consumers, and loss of community. Interestingly, he highlighted the rise of Airbnb as one of the largest causes of current discontent in Berlin, as the rapid expansion of Airbnb rentals leads to gentrification, displacement of local people, housing shortages, and neighbourhoods becoming dominated by temporary visitors to the detriment of local communities.

Fabian Frenzel, a lecturer at the University of Leicester and a research associate with the University of Johannesburg in South Africa, focused on slum tourism. Often viewed as a relatively recent phenomenon originating in the favelas of Rio and the townships of South Africa, he put this form of tourism in a historical context going back to Victorian times, when the better-off would visit and volunteer in early London slums, eventually leading to reform and development. Fabian argued that while some tours can be exploitative, particularly those which display children as photo opportunities, the interest in areas such as the Rio favelas can also bring benefits. Once ignored by authorities and not appearing on city maps, favela tourism has contributed to the acknowledgment, mapping and infrastructure development of these areas. Visitors to favelas can discover that they can be positive places to live and work in, and tourism revenue can help develop infrastructure, provide social services, and create opportunities for new businesses to be established.

CABI’s own Arne Witt gave a presentation on how tourism intersects with one of CABI’s other main areas of work, invasive species. Travel and tourism provide pathways by which invasive species can be introduced and spread in new areas, while invasives can also negatively impact tourism by threatening the biodiversity which brings ecotourists to an area, and increasing conflicts between humans and wildlife. Tourists have carried invasive species to the upper slopes of Mount Kilimanjaro, and to Antarctica, and Arne presented data from the Serengeti/Maasai Mara area of East Africa to show how hotels and lodges are contributing to the spread of invasive plants. Of 245 alien plant species in the area, 211 were intentionally introduced, of which 50 have become naturalized in lodge gardens, and 22 have escaped and become invasive in the ecosystem. Arne raised the concept of increasing homogenization around the world, with hotels giving the same experience wherever you are in the globe, and flora losing its diversity as trade, travel and tourism vastly increase the rate of introduction of new species – now 10-20 new species a year in Hawaii. Unique species and biodiversity are a driver of ecotourism, and where introduction of unpalatable or poisonous species lead to reductions in wildlife, or greater encroachment of farmers and pastoralists into protected areas when pastures and agricultural land are overrun by invasives, then wildlife tourism will decline.

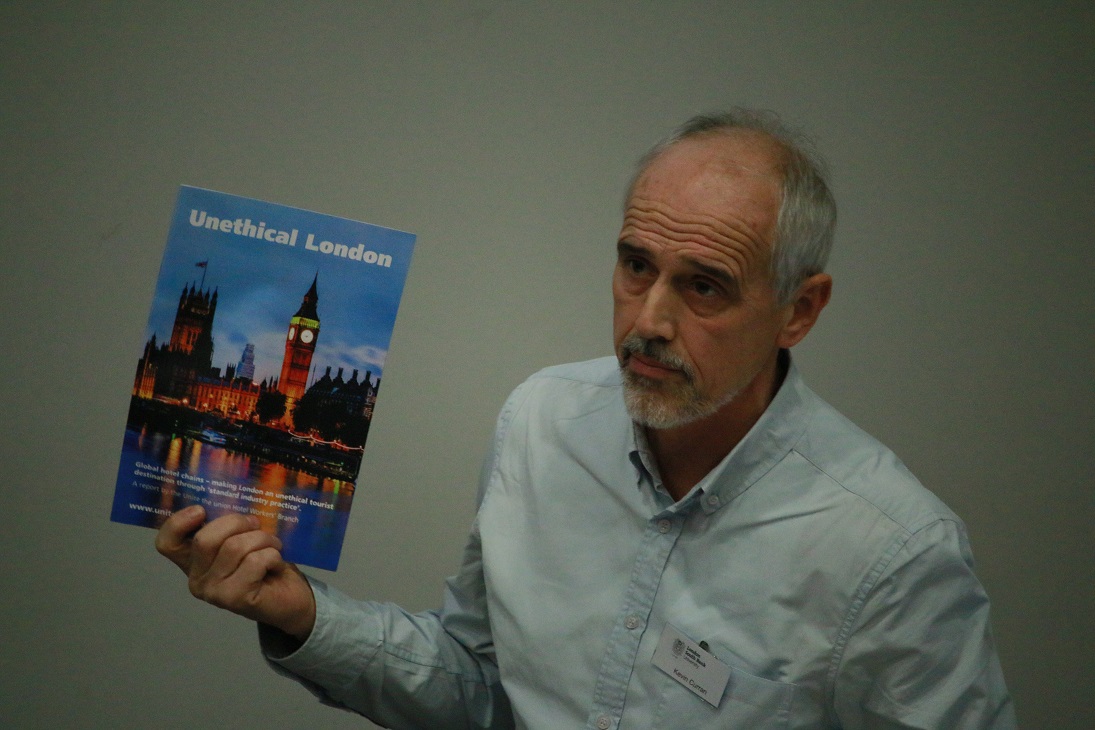

Kevin Curran, from the Central London Hotel Worker’s branch of the union Unite, gave what for many present was an eye-opening presentation about the conditions of hospitality industry employees in London. In a city where hotels are among the most expensive in the world, 68% of hospitality workers earn less than the London Living Wage of £9.40 an hour. 70% are migrants, English is the first language of only a minority, and the structure of the industry where hotel management is often franchised, and services such as catering and housekeeping are frequently outsourced, makes organization of workers and negotiation with employers on pay and conditions fraught with difficulties. Kevin said that while many of the hotel chains present in London have signed social responsibility codes such as the United Nations Global Compact which commit to promoting freedom of association and collective bargaining for staff, in reality the hotels in London refuse workplace access to union organisers, and will not discuss application of the Codes. He contrasted the situation in London with that of hotel workers in New York, where union representation in the industry is widespread, and pay rates are 2.5 times those in London while hours are considerably shorter. For more information, see the report Unethical London (PDF file).

The final speaker for the day was Rebecca Hawkins of the Responsible Hospitality Partnership, which works with businesses to improve sustainability practices and resource efficiency. After several presentations highlighting some of the social and environmental issues in the tourism industry, Rebecca was tasked with reiterating that tourism can be an agent for positive change, while being a complex industry in which the social impacts are more difficult to deal with than more easily measurable impacts such as energy and water use. She pointed out that while many hotel staff are on zero-hours contracts, and the majority in places such as the UK are migrant workers, it is still one of the few industries where it is possible to progress with limited formal qualifications, and set up new businesses without large amounts of capital. The challenge for pursuing social justice is that even global bodies such as the UNWTO are primarily focused on driving growth, and that business leaders are tasked with profit maximization, which leads to outsourcing, franchising and cost-cutting. Corporate Social Responsibility leads to hospitality companies reporting on measurable outputs such as number of hotels environmentally certified, and number of employees trained, but the next and more difficult step is to determine outcomes: how these activities result in positive change, such as better working conditions, and greater income for local communities.

Of the three pillars of tourism sustainability (economic, environmental and social), the social side is the most complex to understand and improve. But tourism is an industry in which, like the other fields in which CABI works, knowledge can be applied to aid improved practices and benefit both livelihoods and the environment. Click here to see what we are doing in leisure and tourism, and our current involvement in the International Year of Sustainable Tourism for Development. See also our Internet Resource on leisure and tourism, which includes over 170,000 abstracts and 130 eBooks.

2 Comments

Leave a Reply

Thank you! I am even more sorry that I could not attend. Congratulations on organising such a valuable event.

This appears to be a fascinating look at Tourism and Social Justice. I wish I had know about the conference – i would have attended.