I believe that waste prevention, reduction, re-use and recycling are key

I believe that waste prevention, reduction, re-use and recycling are key

measures to achieve sustainability in a world which is becoming

depleted of natural resources. These measures will also reduce the

environmental impact of pollution, by reducing carbon emissions and

might even benefit economic growth. For this reason, I attended a

seminar on waste recycling recently to find out the status

of waste reduction through recycling in the UK.

The seminar entitled

‘Valuing Resources: The Science and Economics of Recycling’ was

organised by the UK Parliamentary Office of Science and Technology

(POST). The speakers were: Chris Dow, CEO of Closed Loop Recycling, a

state-of-the-art UK plastics recycling company; Marcus Gover, one of the

directors for WRAP, an organisation helping businesses and individuals reduce

waste, develop sustainable products and use resources in an efficient

way;

and Nat Hunter, co-director of Design at the RSA Action and Research

Centre, who is involved in a project investigating the role of design in

moving the country from a linear to a circular economy.

I was astonished to find out that around 90% of what is produced in a given year will

end up in the dump in the following year. Of course, this will include

products that must be thrown away after use, such as nappies and toilet

tissues, but nevertheless there is a lot of room for reducing what is

thrown away.

It was pleasing to learn that the UK government aims to move to a zero

waste economy to achieve greater sustainability. Probably as a result, the

amount of waste sent to recycling in the UK has seen a 50% increase for

all sectors of the economy since 2004. Landfill tax is the main driving

force. Marcus Gover pointed out that more than 90% of the UK local

authorities are collecting plastics. He gave figures for dry

recyclables, which showed that paper is the most recycled material in

the group (nearly 75% of waste paper being recycled), followed by glass

(more than 60%), aluminium (nearly 50%) and plastics (less than 25%),

but more waste plastic is also exported to other countries, e.g. China.

However, there is more that can be done, since 48% of plastic bottles,

which amounts to 240,000 tonnes are still ending up in landfills. This

is simply due to people not placing these in a recycle bin. Chris Dow

suggested that we need to encourage others who do not recycle to do so.

He also said that greater uniformity of collection would help to solve

the problem of recyclables ending up in landfills. Plastics recycling

process yields value and positive long term impact. Communal collection

is effective, with three times more being collected from a communal

collection systems.

The waste and recycling sector in the UK was valued at £11 billion in

2011 and is forecast to grow by 3-4% a year in this decade (POSTnote

425). From what I heard at the seminar, there is still a lot of

potential to increase the value of the recycling sector further and this

can be done by applying measures, such as taxation and incentives that

will encourage people to make a greater effort to recycle their waste. I believe a scheme, which was (and hopefully still is) used in Brazil, is effective and should be used more widely. The scheme makes sure beverages glass bottles are more expensive than the beverage inside them, which means it is in the customers' interest to return the bottles each time they go to buy those beverages, so as not to have to pay for them each time.

An interesting fact I learned at the seminar is that it takes one tonne of ore

on average to produce 5 grams of gold, but one tonne of discarded

mobile phones can yield a massive 150 grams. Mobile phones consist of

layers of metal and circuit board, all made of 35 types of metal,

including copper, tin, cobalt and gold. An estimated 80 million working mobile phones were retained in UK households, lost in drawers and cupboards, even though there are companies advertising that they want to buy spare mobile phones from people. This suggests we should be making much more of an effort to pass our old mobiles on. Maybe we should not be sold a new mobile phone, unless we can provide an old one as part-exchange! Extreme, I know, but it would make sure more old phones are re-used or recycled.

My favourite quote of the seminar was by Nat Hunter, who said that “waste really is a design flaw!” An article by Sophie Thomas, from RSA, entitled 'The great recovery' explains the concept of building to last.

A briefing paper (POSTnote PN 425) entitled ‘Maximizing the Value of Recycled Materials’ was published to go with the seminar and is available via the POST website. http://www.parliament.uk/business/publications/research/briefing-papers/POST-PN-425

The Cabi Environmental Impact internet resource contains over 400 records on waste recycling, from the CAB Abstracts database, which are linked here for the benefit of subscribers.

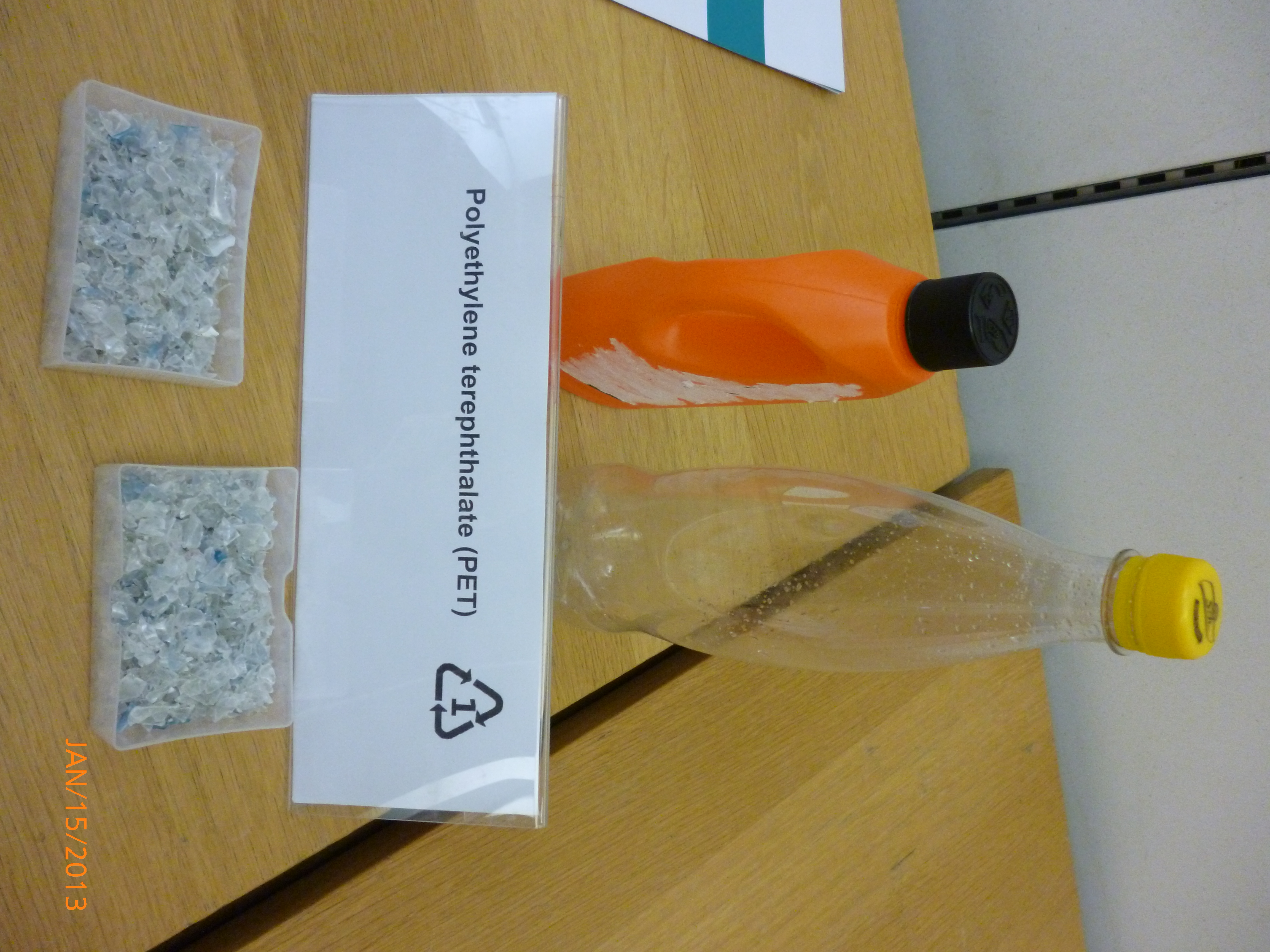

The above photo, by Vera Barbosa, is of an exhibit at the seminar, showing the end-product of Polyethylene terephthalate (PET) bottles recycling, ready to be used in the process of making new PET bottles. Nowadays, around 15% recycled material is included in plastics manufacturing process.

3 Comments

Leave a Reply

You are absolutely right. Using recycled products is the right way. There is no sense in using all the resources that our mother nature provides us. And we may not be able to see the negative part of not recycling but it is bound to affect our future generations. I would certainly not want that for my kids.

Recycle is a great way to protect our nature. But we have to had some sort of system. We don’t have system on recycling. All of us know it, but we don’t know where to go.

very good. thank you…