If you’ve been to Thailand recently you probably enjoyed a week or two in a stunningly beautiful country with great tropical weather and lots of interesting culture. What’s more you were probably relieved to be able to enjoy all this without the inconvenience of taking anti-malarial drugs every day unlike many other tropical destinations. However, this may change in future, especially if you’re planning to go to the northeast of the country.

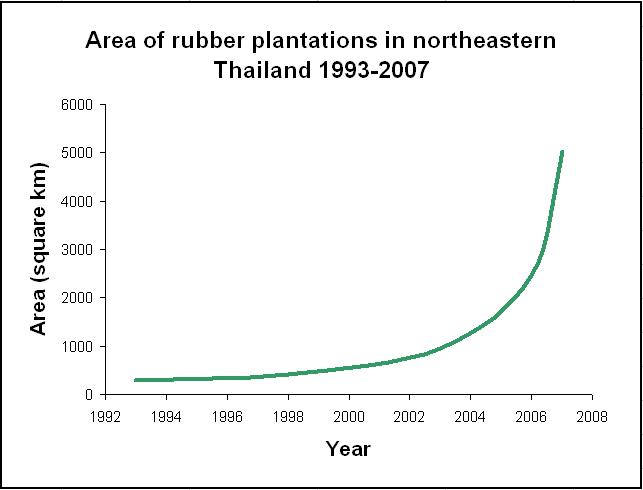

A recent article in the journal Emerging Infectious Diseases predicts that malaria may re-emerge in northeastern Thailand due to the recent, rapid increase in rubber (Hevea brasiliensis) plantations in this area. According to Trevor Petney and colleagues, the area covered by rubber plantations has increased from ~284 km² in 1993 to 948 km² in 2003 and to 5,029 km² by 2007. This exponential increase is due to the major economic importance of natural rubber – it cannot be replaced by synthetic alternatives and so the demand for and production of this commodity has consistently increased.

A recent article in the journal Emerging Infectious Diseases predicts that malaria may re-emerge in northeastern Thailand due to the recent, rapid increase in rubber (Hevea brasiliensis) plantations in this area. According to Trevor Petney and colleagues, the area covered by rubber plantations has increased from ~284 km² in 1993 to 948 km² in 2003 and to 5,029 km² by 2007. This exponential increase is due to the major economic importance of natural rubber – it cannot be replaced by synthetic alternatives and so the demand for and production of this commodity has consistently increased.

The main vector mosquito in this area, Anopheles dirus sensu stricto (pictured left), is forest dwelling and requires a shaded environment for its survival and reproduction. For this reason, malaria incidence decreased dramatically in the early 1900s due to deforestation in northeastern Thailand. Currently autochthonous malaria cases are restricted to 3 provinces that border Cambodia and Laos (Sisaket, Ubon Ratchathani, and Surin – see map below) and around a third of these cases are imported.

The main vector mosquito in this area, Anopheles dirus sensu stricto (pictured left), is forest dwelling and requires a shaded environment for its survival and reproduction. For this reason, malaria incidence decreased dramatically in the early 1900s due to deforestation in northeastern Thailand. Currently autochthonous malaria cases are restricted to 3 provinces that border Cambodia and Laos (Sisaket, Ubon Ratchathani, and Surin – see map below) and around a third of these cases are imported.

Mosquitoes are sensitive to changes in environmental conditions, such as shade, temperature, and humidity and new rubber plantations provide more suitable habitat for A. dirus s.s. than rice paddies and possibly even better than the original rain forests. On top of this, the greatly reduced contact between the local human population and Plasmodium spp. over the past ~50 years suggests that malaria would enter a highly susceptible population. And to add to the problem, several strains of Plasmodium in Thailand and surrounding countries are multidrug resistant, which leads to treatment difficulties.

Mosquitoes are sensitive to changes in environmental conditions, such as shade, temperature, and humidity and new rubber plantations provide more suitable habitat for A. dirus s.s. than rice paddies and possibly even better than the original rain forests. On top of this, the greatly reduced contact between the local human population and Plasmodium spp. over the past ~50 years suggests that malaria would enter a highly susceptible population. And to add to the problem, several strains of Plasmodium in Thailand and surrounding countries are multidrug resistant, which leads to treatment difficulties.

Trevor Petney points out the need to incorporate these predictions into future planning and control: “Although the association between rubber plantations and malaria is well known in Southeast Asia, the potential for reemergence should receive substantially more attention from economic, agricultural, and environmental planning bodies… Understanding the influence of land use change on malaria occurrence is critical for shaping future surveillance and control strategies.”

Reference:

Trevor Petney, Paiboon Sithithaworn, Rojchai Satrawaha, Carl Grundy-Warr, Ross Andrews, Yi-Chen Wang, and Chen-Chieh Feng (2009) Potential Malaria Reemergence, Northeastern Thailand. Emerging Infectious Diseases 15 (8), 1330-1331.

For more information about the links between land use change and malaria, here’s a selection of relevant articles – abstracts are all available on CAB Abstracts or Global Health databases:

Yasuoka, J.; Levins, R. (2007) Impact of deforestation and agricultural development on anopheline ecology and malaria epidemiology. American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene 76 (3), 450–60.

Lindblade, K. A.; Walker, E. D.; Onapa, A. W.; Katungu, J.; Wilson, M. L. (2000) Land use change alters malaria transmission parameters by modifying temperature in a highland area of Uganda. Tropical Medicine and International Health 5 (4), 263–274.

Munga, S.; Yakob, L.; Mushinzimana, E.; Zhou, G. F.; Ouna, T.; Minakawa, N.; Githeko, A.; Yan, G. Y. (2009) Land use and land cover changes and spatiotemporal dynamics of anopheline larval habitats during a four-year period in a highland community of Africa. American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene 81 (6), 1079-1084.

Patz, J. A.; Olson, S. H. (2006) Malaria risk and temperature: influences from global climate change and local land use practices. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 103 (15), 5635-5636.

Nguyen Hong Sanh; Nguyen Van Dung; Nguyen Xuan Thanh; Trieu Nguyen Trung; Truong Van Co; Cooper, R. D. (2008) Forest malaria in Central Vietnam. American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene 79 (5), 652-654.

Póvoa, M. M.; Conn, J. E.; Schlichting, C. D.; Amaral, J. C. O. F.; Segura, M. N. O.; Silva, A. N. M. da; Santos, C. C. B. dos; Lacerda, R. N. L.; Souza, R. T. L. de; Galiza, D.; Santa Rosa, E. P.; Wirtz, R. A. (2003) Malaria vectors, epidemiology, and the re-emergence of Anopheles darlingi in Belém, Pará, Brazil. Journal of Medical Entomology 40 (4), 379-386.

Ayala, D.; Costantini, C.; Ose, K.; Kamdem, G. C.; Antonio-Nkondjio, C.; Agbor, J. P.; Awono-Ambene, P.; Fontenille, D.; Simard, F. (2009) Habitat suitability and ecological niche profile of major malaria vectors in Cameroon. Malaria Journal 8 (307).

Turell, M. J.; Sardelis, M. R.; Jones, J. W.; Watts, D. M.; Fernandez, R.; Carbajal, F.; Pecor, J. E.; Klein, T. A. (2008) Seasonal distribution, biology, and human attraction patterns of mosquitoes (Diptera: Culicidae) in a rural village and adjacent forested site near Iquitos, Peru. Journal of Medical Entomology 45 (6), 1165-1172.

Overgaard, H. J.; Ekbom, B.; Suwonkerd, W.; Takagi, M. (2003) Effect of landscape structure on anopheline mosquito density and diversity in northern Thailand: implications for malaria transmission and control. Landscape Ecology 18 (6), 605-619.

1 Comment

Leave a Reply

guys!please tell me the uses of rubber plantations