It's not cucumbers, it might be beansprouts? E. coli O104 has killed 22 people so far, made over1400 ill and reached 11 countries. It has had a significant effect on two countries- damaging Spain’s economy and damaging the credibility of the German public health system. The fallout is broader still: the EU – and that includes us - is now offering compensation to Spanish farmers – using a central fund.

For the bewildered public, the clue is in the name Escherichia coli…coli, Latin for intestine; for these bacteria live in the gut of man and warm-blooded animals. Unfortunately, some strains (STEC/VTEC, see Outbreak of E. coli acronyms in Germany) produce toxins that can cause severe diarrhoea, and this is always down to someone’s lack of hygiene.

Not washing hands after defecation, using a water supply contaminated with faeces to wash or water crops or poor manure preparation. It’s transmitted because poo was on your fingers or on your food and went into your mouth!

In the UK we have had outbreaks in the past of Ecoli O157 (another strain) linked to children’s petting farms and to a butchers’ as have Germany and other European countries. There are two factors that make the latest German outbreak different: one, it’s a modified, nastier version of O104 and two the release of public information has been ineptly handled.

The authorities very quickly identified the bacteria, although identifying the strain and why it was so virulent took a little longer; the point being that the immediate issue of advice to thoroughly wash vegetables and fruit eaten raw has limited the outbreak (truly!).

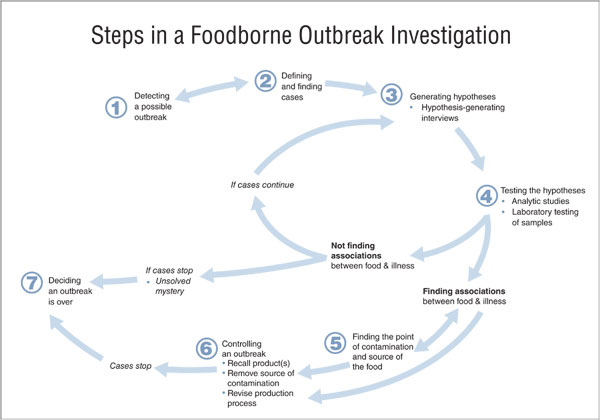

But why is it taking so much longer to tie down the actual source of the disease, the “ground zero” as the popular press are describing it? The diagram below shows the steps for a food-borne outbreak investigation taken from the Centers for Disease Control & Prevention (CDC) website in the USA.

Steps 2, 4 and 5 rely on identifying the disease organism and for this we now have rapid tests (but they still require a lab). With test strips or PCR you can rapidly identify which strain of the bacteria & you can now also determine virulence and antibiotic resistance.

But it’s still more common to do virulence through culturing the bacteria in petri dishes containing red blood cells to see if they lyse (burst), indicating that the bacteria can cause HUS (haemolytic uremic syndrome , which can kill). That would still only take about 2 lab-days?

The real rate-limiting steps are 3 and 5: finding the source. Step 3 means interrogating some very sick people as to what they ate in the 2-3 days before they became ill. Can you remember that?

You look for a common food or common eating venue for these cases. With this outbreak you make the link to a vegetarian diet and raw food, BUT you don’t know which fruit or salad vegetable. As a public health practitioner, you should be aware from your training, from your reporting authority, or from health databases such as Global Health, that the usual suspects therefore are tomatoes, cucumbers or bean sprouts. You immediately start some control measures (part of step 6) advising the public to wash such produce before consumption.

Having identified some food suspects & their origins, its onto step 5.

You sample the production line…the soil from a number of locations in the field or greenhouse, the plants, the seed, the washing process, the human food-handlers. You test them all and hope! Thus, the latest report that first results from a German bean sprout farm have proved negative is perhaps not quite providing the all-clear that the Spanish cucumbers were finally given.

The tomato-linked outbreak in the US (2008) subsided & disappeared from the headlines in weeks but it took 4 months to finally tie down the specific source to…jalapeno peppers.

So let the epidemiologists and public health practitioners get on with their job. They are going as fast as they can. And remember to follow their advice to wash raw vegetables &fruit, and to wash your hands!

Below are articles from Global Health which give examples of the latest rapid tests, methods for sterilising seeds, water & equipment, and also UV systems to check for urine & faecal contamination.

A related blog looks at ways of changing people’s hand washing behaviour.

Resources from CABI

Found on Global Health database:

Rapid tests

Unearthing human pathogens at the agricultural-environment interface: a review of current methods for the detection of Escherichia coli O157 in freshwater ecosystems

Sterilising seeds & water

Determination and improvement of microbial safety of wheat sprouts with chemical sanitizers

Inactivation of Escherichia coli O157:H7 attached to spinach harvester blade using bacteriophage

Checking for faecal contamination using UV

Related blog: Handwashing: harnessing the yuck factor to improve public health

Related News & Blogs

CABI’s GRASP Fellowship awardee working in partnership to help increase food safety in Uganda’s urban markets

Dr Monica Kansiime, who was awarded a Gender Responsive Agriculture Systems Policy (GRASP) Fellowship aimed at improving policy process in agri-food systems, is working in partnership to help increase food safety in Uganda’s urban fresh fruits and vege…

30 January 2024